NSU Research Activity and Scholarship Earns R1 Designation

Nova Southeastern University, the state's largest private research university, has received an R1 designation by the Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education. This elite status is given to universities reaching the highest levels of research activity, research funding, and doctoral degrees awarded. Find out more about the impact this distinction will have for faculty, students, and the community.

Elevating Our Impact

Since our founding, Nova Southeastern University, Florida’s largest private research university, has stood as a beacon of knowledge and innovation, a crucible of intellectual exploration, and a catalyst for positive change. We believe in pushing the boundaries of knowledge and driving innovation through groundbreaking research. Our research community is committed to exploring new frontiers, tackling complex challenges, and making a lasting impact on the world. These values—and a commitment to improve our world—are baked into our collective DNA.

NSU researchers are world-renowned experts in health care research, leading the fight against cancer, neuroimmune diseases, and autism. And our marine scientists are at the forefront in addressing issues of the environment and climate change, as well as in groundbreaking research into saving our sea life and protecting our oceans.

NSU Research By the Numbers

Every Discovery is a Step Toward Improvement

Join us in our journey to explore and expand the frontiers of knowledge. For our faculty, research may be local but the reach is global. Their work shapes the world and instills a passion for research in our students. Together, we can pioneer a future that knows no bounds—harnessing the best within ourselves to deliver impact in the areas that matter most.

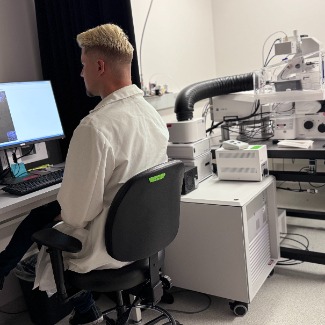

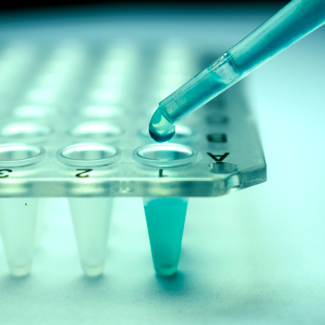

World-Class Research Facilities Excite Discoveries

NSU’s specialized research facilities fuel creativity and innovation. Our scientists collaborate on cutting-edge projects that address global issues and shape the future. With access to advanced and innovative technologies, they foster solutions in health care and biotechnology, as well as in environmental, life, and social sciences.

They are leading hundreds of basic, applied, and clinical research projects to improve patient care, make new drug discoveries, reduce mental health disorders, and examine the forces that affect our oceans.

A public-private partnership between NSU and Broward County.

Alan B. Levan | NSU Broward Center for InnovationWorking to eradicate breast cancer through prevention and the development of new clinical strategies.

AutoNation Institute for Breast Cancer Research & CareContributing to sea turtle conservation through beach monitoring, providing data, and active community engagement.

Broward County Sea Turtle Conservation ProgramA brain center with heart and soul focused on providing comprehensive and compassionate patient care.

David and Cathy Husman Neuroscience Institute at NSU HealthA collaboration dedicated to the science-based conservation of marine fish populations and biodiversity.

Guy Harvey Research InstituteAdvancing knowledge and caring for people with complex neuro-inflammatory illnesses.

Institute for Neuro-Immune MedicineShowcasing the programming, research, and scholarly activities in the field of early childhood and special education.

Marilyn Segal Early Childhood Studies CenterA public education facility offering programs on sea turtle conservation and coastal ecology topics.

Marine Environmental Education Center (MEEC)Researchers assess, monitor, and restore coral reefs.

National Coral Reef InstituteDedicated to enhancing human health by advancing innovative cell-based therapies.

NSU Cell Therapy InstituteCommitted to developing anti-cancer therapies with the aim of moving novel compounds to market in the shortest time possible.

Rumbaugh-Goodwin Institute for Cancer ResearchConducting targeted and impactful research to improve management, conservation, recovery, and understanding of the world’s sharks and rays.

Save Our Seas Shark Research Center250+ Sponsored Research Projects at NSU

Addressing Critical Areas Such As Anticancer Therapies, Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, Coral Reef Restoration, Stem Cells, Shark DNA Forensics, and More

Research at NSU is supported by 100+ external agencies, including the National Science Foundation, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Education, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association, and the Department of Defense.

NSU is only 1 of 59 universities nationwide recognized by the Carnegie Foundation for both High Research Activity and Community Engagement.

Enriching the Next Generation of Leading Researchers

We believe in empowering the next generation of researchers. Faculty researchers support student success through mentorship to cultivate the next generation of scholars and professionals. Our collaborative teams of undergraduates, graduate students, and faculty are examining the intricate problems of our contemporary world. NSU students engage in complex, societal issues, explore their intellectual curiosities, and make a meaningful impact on society.

An Interdisciplinary Approach That Fosters Collaboration

As a leading research university, we are dedicated to the advancement of human knowledge, the pursuit of truth, and the betterment of society. By embracing the intersection of art, culture, and science, NSU contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of the world around us.

Research Projects Can Be Found Throughout Our Colleges

College of Computing and Engineering

Halmos College of Arts and Sciences

Innovation and Impact

Learn about the tangible outcomes of our research efforts and how they are making a real difference in the world. From patents and publications to industry partnerships, our commitment to innovation ensures our research has a lasting impact beyond the academic realm.

Saving Our Seas

Join Us in Shaping the Future

Whether you're a prospective student, a collaborator from another institution, or someone passionate about supporting groundbreaking research, there are many ways to get involved. Join us on the journey of discovery and be a part of shaping the future through research at NSU.

Research News